This lovely profile on our Professor Baba was a chapter in the book People called Mumbai, curated by Nisha Nair-Gupta which you can buy on Amazon.

The capoeirista has

the coordination of a dancer,

the flexibility of a gymnast,

the strength of a martial artist,

the endurance of a marathon runner,

the beat of a drummer

and the heart of a philosopher.

Today, people flock to martial arts classes for various reasons—some want to stay fit, some want to learn self-defence and others are looking for a way to counter the stress of urban living.

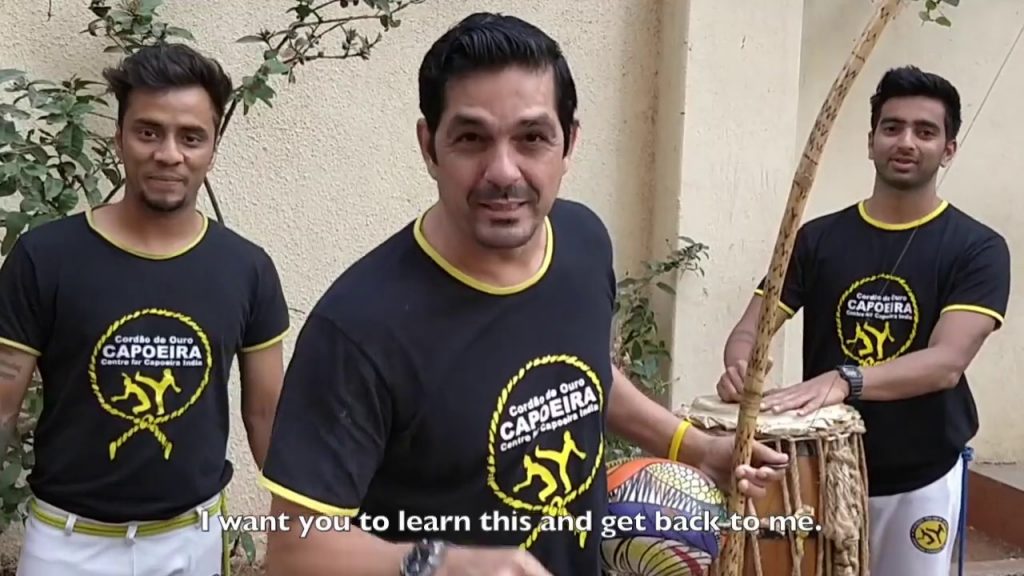

In a nondescript lane in Khar is a studio space, the first Indian centre of Capoeira Cordao de Ouro headed by Instructor Baba, an energetic, charismatic 40-something man with fitness and flexibility levels that belie his age. His enthusiasm and energy transcend the Bandra studio and infect every student in his class. The group of about 30 students is bubbling with excitement. Practising a non-violent, escape-oriented means of self-defence, Capoeiristas move agilely to the beat of drums and the tune of a traditional slave song sung in Portuguese by those standing around. The rhythmic clapping and cheering resonate through the room; the euphoria is palpable. With all its excitement and energy, the session looks more like a dance routine than a fight. They call it “playing Capoeira”.

With its non-violent philosophy, social nature, music and dance-like movements, Capoeira, which originated in Brazil, fits the Indian ethos, though it was introduced to the country only in 2006 by Reza Baba Massah, a Capoeirista who learned the art form in Israel. He is known simply as “Baba” in Capoeira circles.

Speaking to a new batch of students Baba says, “Capoeira has made me what I am. It has become a way of life for me.” They listen attentively. “I initially wanted to be a pilot and went to Australia to train. I travelled to Canada to complete the required flying hours and that was where I first watched Capoeira. There were a few Christian missionaries standing on the street holding placards about Jesus and next to them was a group of men of African origin, doing back-flips, kicks, ducks and handstands in a seemingly coordinated way, with others beating drums and singing around them. I did not know about Capoeira at the time and thought to myself, 'What on earth are these men doing?' But my interest had been aroused. The men exuded a positive energy that drew me and I was fascinated by their vibrancy, moves and flexibility. I could not get it out of my head for a long time!”

Baba was hooked. “I returned to Israel, where finding a pilot's job was slow progress, so I decided to open a cafe, since my other passion was cooking. I set up a cafe in a mall, but as luck would have it, on the day of the opening there was a bomb blast in the city. People were scared and stayed at home and the mall was deserted. No friends or family turned up for the opening. There was one area in the mall, however, which was buzzing with activity — a fitness studio near my cafe. Hearing music, clapping and cheering, I peered through the blinds and saw the room packed with people playing Capoeira, unfazed by the bombs. There was a high level of energy and a cheerful vibe in the room. I thought, “If these people are here for their class even today, they would make ideal patrons for my new cafe!” In my attempt to befriend them, I struck a deal with the head instructor of the class, Mestre Cueca. It was decided that I would join his Capoeira class and he, in turn, would eat at my cafe regularly. I started attending the class and before I knew it, I was hooked.” It was Mestre Cueca who named him Baba and in turn, Baba gives each of his students a Capoeira name.

Baba met his wife on a visit to Bombay. He was on his way to Sterling cinema for a movie and lost his way. A young lady helped him with directions, they became friends, fell in love and got married. She moved to Israel to live with him. It was her idea to bring Capoeira to India. Speaking to her friends in Mumbai, she realised that no one in the city knew about it. A Google search on Capoeira India found just one result: Akshay Kumar had listed it as one of the seven deadliest martial arts. Today the same search leads to five pages of results about Baba's training centres and his students!

Baba and his wife saw potential in India for Capoeira training and also hoped to open a restaurant in Mumbai. They moved to the city in 2005. Once again the restaurant did not work out, but in 2006 Baba set up a Capoeira centre in Bandra and started teaching. His first class had four students. For the next four years, Baba taught adults. The number of students grew steadily; people were drawn to the art form because of its universal appeal and philosophy. Just as the slaves had used Capoeira to alleviate trauma, people turn to Capoeira today to help deal with their urban frustration and stress. While training, they are able to shut out the problems of the outside world, and they leave the class feeling rejuvenated and alive.

Capoeira developed as an underground art form in Brazil, created by African slaves who needed a way to deal with the repression of slavery. It emphasised escape moves and gave its practitioners hope. In Israel, drawn by its universal appeal, Muslims and Jews play Capoeira together and relish the sense of community formed within the group. In Mumbai, many students in Baba's group are young professionals who have migrated to the city from elsewhere. Through Capoeira, strong bonds are formed between these individuals and they become a family of sorts, supporting one another in a new environment.

“Training just adults was not very profitable, since several of my students are broke. But after watching my own son take to Capoeira, I started teaching children as well and soon found it very rewarding. Since children are more flexible, they are able to learn quicker and there are many more takers in the younger age groups. Capoeira is both practical and relevant today, with all the bullying and child molestation. It is i workout for the entire body and combined with its non-violent philosophy, it makes a good alternative to regular PE sessions in schools,” Baba explains. He clarifies that Capoeira teaches children not to pick a fight, but how to get out of one. Several Mumbai schools have already included Baba's Capoeira programme as part of their curriculum.

Baba and his group also work with many Mumbai-based NGOs, conducting workshops for children from Dharavi, the Khar slum and orphanages and children of sex workers. These underprivileged kids are the most receptive and eager to learn. Baba and his troupe are examples of how Capoeira can change life—they give hope to these children, a means of escape from their disadvantaged lives, while having fun with an activity that challenges physical abilities. Where college graduates are hesitant, these children, with fewer opportunities, might take their knowledge of Capoeira to another level by becoming instructors themselves, Baba hopes.

Several of Baba's adult students have already started teaching the martial art form; a young MBA graduate and an engineer are just two of the students who have chosen it as a full time job. It has become more than just a hobby; it is now a way of life for them, which they find more satisfying than any desk job.

As awareness of Capoeira grows in the city, more people are including it in their fitness regimen, with Baba's students-turned-instructors teaching even Bollywood personalities—Aamir Khan, for instance, learned the form for his film Dhoom 3. Cordao de Ouro now has 16 centres around the city and has even spread its arms to Bangalore and Goa.

Spreading a smile, telling stories through movement and song, Capoeira is, Baba says, “like food—it feeds you with vibrations, energy and joy”.

The Cordao de Ouro group does shows along Carter Road in Bandra, beating drums, strumming berimbaus, clapping and singing, while pairs take turns to play Capoeira in the centre of the circle. They will always draw a curious audience, people who are more than happy to join in the fun.